Lie detectors are creeping into UK policing and they still don't work - Wired.co.uk

Lie detectors are creeping into UK policing and they still don't work - Wired.co.uk |

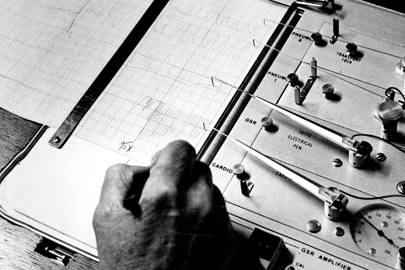

| Lie detectors are creeping into UK policing and they still don't work - Wired.co.uk Posted: 09 Sep 2020 12:00 AM PDT  Ira Gay Sealy / The Denver Post via Getty Images Until recently, the most famous application of the polygraph machine in the United Kingdom was probably the Jeremy Kyle Show. Unlike in the United States, where there are an estimated three million tests a year, the so-called 'lie detector' has never really caught on in Britain. But that's starting to change. The machine – which measures breathing, heart rate, blood pressure and sweat in an attempt to detect deception – is slowly creeping into British policing. Since 2007, it's been used with sex offenders to assess whether they are likely to reoffend if released. Now, two bills working their way through Parliament are set to expand the use of the polygraph further. The first targets domestic abusers deemed at high-risk of causing serious harm. The Domestic Abuse Bill makes provisions for a three-year pilot study during which 300 offenders will take a lie detector test three months after release, and then every six months after that. They won't be jailed for failing the test – but could be if they refuse to take it, or if they try to trick it, according to the Home Office, or if the test shows their risk has escalated. The second is the Counter Terrorism Bill, which will impose mandatory polygraph examinations on high risk offenders who have previously been convicted of terror-related offences. Introducing polygraph tests in these situations is one of 50 recommendations made in response to the 2019 London Bridge attack perpetrated by Usman Khan, who was out on licence when he killed two people and injured three others. But there's a big lack of transparency around the extent to which the polygraph is already being used by police forces and probation services in this country, according to the authors of a new piece of research. Marion Oswald and Kyriakos Kotsoglou of Northumbria Law School sent Freedom of Information Act requests to all UK police forces asking if and how they were using the polygraph. They were largely reluctant to provide details. Of the 46 replies, 37 issued a 'neither confirm not deny' response – an option open to public bodies if they believe that releasing the information would be exempt under the transparency law. Exemptions can be used if releasing information could pose a potential operation or security risk. After requests for the initial decisions to be reviewed, some forces stated that they do not use the polygraph in an 'overt' capacity, although they did not explain what they meant by that term. The researchers say this means police forces could be using polygraphs in "investigatory work or in some covert context". Only five forces – Gwent Police, Merseyside Police, Police Scotland, Wiltshire Police and The Port of Dover Police – denied the use of polygraphs entirely. "I don't think we can tell exactly how police forces are using the polygraph, and that's a concern," says Oswald. The direction of travel is clear, however. Although a 2014 statement from the Association of Chief Police Officers (now the National Police Chief's Council) strongly discourages its use, and the polygraph is not admissible as evidence in court, there is no legal framework to stop police forces attempting to use it during interrogations or as part of an evidence gathering process in the UK. It has, for example, been trialled with individuals suspected (but not convicted) of committing an online sexual offence. During their research, Oswald and Kotsoglou also discovered that Hertfordshire Police was using a polygraph as a bail condition in association with a non-custodial sentence as part of its C2 rehabilitation programme. "There is no legislation that covers the use of the polygraph in that way," says Oswald. At the time of writing Hertfordshire Police had not responded to a request for comment on their use of the system. The reason Oswald, Kotsoglou and others are so concerned about the proliferation of the polygraph is that the research shows that it doesn't work, and that the justifications for the use of the test are undermined by how it's actually been used in practice. Polygraph tests have been repeatedly debunked in independent studies dating back decades. "We cannot stress enough that ever since the first deployment of the polygraph, appellate courts, scientific organisations, and last but not least academic discourse have continuously and nearly unanimously criticised, and rejected this method as unscientific," write Oswald and Kotsoglou. Although they can help coerce suspected criminals into making confessions – and indeed the use of the polygraph with sex offenders has led to an increase in information disclosed during interviews – there's often no way of testing whether those confessions are actually accurate. It has been criticised as a tool of psychological torture. "If you put pressure on people, they will tell you whatever they think you want them to tell you," says Kotsoglou. "This destroys the evidential value of the statement." The machine is also relatively easy to beat with a little training and organisation, which raises questions over its efficacy with suspected terrorists in particular. "Deciding whether to release an offender into the community is difficult, and this looks like a solution which gives you some certainty," says Kotsoglou. "But it's based completely on a false premise." There appears to be little consistency in how the tests are applied and conducted in different areas, according to the researchers. Some forces are using their own officers, while others are outsourcing the tests to external examiners. The Home Office claims its examiners are highly trained and carefully scrutinised – but in truth, most police forces are using the guidelines and training set down by the American Polygraph Association. "There is no independent objective measure," says Oswald. It is, she argues, the equivalent of the polygraph industry marking its own homework. Other concerns include the danger that polygraph tests could shift from being used to corroborate other forms of evidence into a way to pressure the defendant into giving up information, which could be used to obtain a search warrant and secure evidence in a non-objective manner already influenced by a flawed test result, says Kotsoglou. The government knows all this. The drawbacks of polygraphs have been debated in parliament as far back as the 1980s. But the lie detector is a convenient measure for governments to turn to when they need to look tough on crime and want easy PR wins – it's no coincidence that sex offenders, domestic abusers and terrorists are the three groups at the forefront of polygraph use in this country. The SNP sparked tabloid fury recently for daring to raise concerns. There are some cases where the polygraph may be useful – in determining whether a rehabilitation programme is working, for example. "The challenges posed in monitoring terrorist offenders are such that polygraph testing is a sensible additional tool," the UK's Independent Reviewer of Terrorism Legislation recently said in response to the government's planned changes. But its slow creep into policing is alarming, and using it as a means to detect whether a terror suspect is telling the truth is deeply problematic. In their paper, Oswald and Kotsoglou argue for an urgent halt on any further use of the polygraph, along with an independent, public investigation into its current use – with regulation, independent oversight and scrutiny. "We are already on the slippery slope with regards to the polygraph," says Kotsoglou. He calls it zombie forensics, and agues that the polygraph will give society a false sense of security based on an unscientific method. "This becomes a threat in terrorism," he says. "A false sense of security could have literally fatal consequences." Amit Katwala is WIRED's culture editor. He tweets from @amitkatwala More great stories from WIRED🐾 A liver disease is putting the Skye Terrier's existence at risk. Doggy DNA banks could help save it 🔞 As AI technology gets cheaper and easier to use, deepfake porn is going mainstream 🏡 Back at work? So are burglars. Here's the tech you need to keep your home safe 🔊 Listen to The WIRED Podcast, the week in science, technology and culture, delivered every Friday 👉 Follow WIRED on Twitter, Instagram, Facebook and LinkedIn |

| Lie detectors have always been suspect. AI has made the problem worse. - MIT Technology Review Posted: 13 Mar 2020 12:00 AM PDT MMU put out a press release in 2003 touting the technology as a new invention that would make the polygraph obsolete. "I was a bit shocked," Rothwell said, "because I felt it was too early." The US government was making numerous forays into deception-detection technology in the first years after 9/11, with the Department of Homeland Security (DHS), Department of Defense (DoD), and National Science Foundation all spending millions of dollars on such research. These agencies funded the creation of a kiosk called AVATAR at the University of Arizona. AVATAR, which analyzed facial expressions, body language, and people's voices to assign subjects a "credibility score," was tested in US airports. In Israel, meanwhile, DHS helped fund a startup called WeCU ("we see you"), which sold a screening kiosk that would "trigger physiological responses among those who are concealing something," according to a 2010 article in Fast Company. (The company has since shuttered.) Bandar began trying to commercialize the technology. Together with two of his students, Jim O'Shea and Keeley Crockett, he incorporated Silent Talker as a company and began to seek clients, including both police departments and private corporations, for its "psychological profiling" technology. Silent Talker was one of the first AI lie detectors to hit the market. According to the company, last year technology "derived from Silent Talker" was used as part of iBorderCtrl, a European Union–funded research initiative that tested the system on volunteers at borders in Greece, Hungary, and Latvia. Bandar says the company is now in talks to sell the technology to law firms, banks, and insurance companies, bringing tests into workplace interviews and fraud screenings. Bandar and O'Shea spent years adapting the core algorithm for use in various settings. They tried marketing it to police departments in the Manchester and Liverpool metropolitan areas. "We are talking to very senior people informally," the company told UK publication The Engineer in 2003, noting that their aim was "to trial this in real interviews." A 2013 white paper O'Shea published on his website suggested that Silent Talker "could be used to protect our forces on overseas deployment from Green-on-Blue ('Insider') attacks." (The term "green-on-blue" is commonly used to refer to attacks Afghan soldiers in uniform make against their erstwhile allies.) The team also published experimental results showing how Silent Talker could be used to detect comprehension as well as detection. In a 2012 study, the first to show the Silent Talker system used in the field, the team worked with a health-care NGO in Tanzania to record the facial expressions of 80 women as they took online courses on HIV treatment and condom use. The idea was to determine whether patients understood the treatment they would be getting—as the introduction to the study notes, "the assessment of participants' comprehension during the informed consent process still remains a critical area of concern." When the team cross-referenced the AI's guesses about whether the women understood the lectures with their scores on brief post-lecture exams, they found it was 80% accurate in predicting who would pass and who would fail.

The Tanzania experiment was what led to Silent Talker's inclusion in iBorderCtrl. In 2015, Athos Antoniades, one of the organizers of the nascent consortium, emailed O'Shea, asking if the Silent Talker team wanted to join a group of companies and police forces bidding for an EU grant. In previous years, growing vehicle traffic into the EU had overwhelmed agents at the union's border countries, and as a result the EU was offering €4.5 million ($5 million) to any institution that could "deliver more efficient and secure land border crossings ... and so contribute to the prevention of crime and terrorism." Antoniades thought Silent Talker could play a crucial part. When the project finally announced a public pilot in October 2018, the European Commission was quick to tout the "success story" of the system's "unique approach" to deception detection in a press release, explaining that the technology "analyses the micro-gestures of travelers to figure out if the interviewee is lying." The algorithm trained in Manchester would, the press release continued, "deliver more efficient and secure land border crossings" and "contribute to the prevention of crime and terrorism." The program's underlying algorithm, O'Shea told me, could be used in a variety of other settings—advertising, insurance claim analysis, job applicant screening, and employee assessment. His overwhelming belief in its wisdom was hard for me to share, but even as he and I spoke over the phone, Silent Talker was already screening volunteers at EU border crossings; the company had recently launched as a business in January 2019. So I decided to go to Manchester to see for myself. Silent Talker's offices sit about a mile away from Manchester Metropolitan University, where O'Shea is now a senior lecturer. He has taken over the day-to-day development of the technology from Bandar. The company is based out of a blink-and-you'll-miss-it brick office park in a residential neighborhood, down the street from a kebab restaurant and across from a soccer pitch. Inside, Silent Talker's office is a single room with a few computers, desks with briefcases on them, and explanatory posters about the technology from the early 2000s. When I visited the company's office in September, I sat down with O'Shea and Bandar in a conference room down the hall. O'Shea was stern but slightly rumpled, bald except for a few tufts of hair and a Van Dyke beard. He started the conversation by insisting that we not talk about the iBorderCtrl project, later calling its critics "misinformed." He spoke about the power of the system's AI framework in long, digressive tangents, occasionally quoting the computing pioneer Alan Turing or the philosopher of language John Searle. "Machines and humans both have intentionality—beliefs, desires, and intentions about objects and states of affairs in the world," he said, defending the system's reliance on an algorithm. "Therefore, complicated applications require you to give mutual weight to the ideas and intentions of both." O'Shea demonstrated the system by having it analyze a video of a man answering questions about whether he stole $50 from a box. The program superimposed a yellow square around the man's face and two smaller squares around his eyes. As he spoke, a needle in the corner of the screen moved from green to red when he gave false answers, and back to a moderate orange when he wasn't speaking. When the interview was over, the software generated a graph plotting the probability of deception against time. In theory, this showed when he started and stopped lying.

The system can run on a traditional laptop, O'Shea says, and users pay around $10 per minute of video analyzed. O'Shea told me that the software does some preliminary local processing of the video, sends encrypted data to a server where it is further analyzed, and then sends the results back: the user sees a graph of the probability of deception overlaid across the bottom of the video. According to O'Shea, the system monitors around 40 physical "channels" on a participant's body—everything from the speed at which one blinks to the angle of one's head. It brings to each new face a "theory" about deception that it has developed by viewing a training data set of liars and truth tellers. Measuring a subject's facial movements and posture changes many times per second, the system looks for movement patterns that match those shared by the liars in the training data. These patterns aren't as simple as eyes flicking toward the ceiling or a head tilting toward the left. They're more like patterns of patterns, multifaceted relationships between different motions, too complex for a human to track—a typical trait of machine-learning systems. The AI's job is to determine what kinds of patterns of movements can be associated with deception. "Psychologists often say you should have some sort of model for how a system is working," O'Shea told me, "but we don't have a functioning model, and we don't need one. We let the AI figure it out." However, he also says the justification for the "channels" on the face comes from academic literature on the psychology of deception. In a 2018 paper on Silent Talker, its creators say their software "assumes that certain mental states associated with deceptive behavior will drive an interviewee's [non-verbal behavior] when deceiving." Among these behaviors are "cognitive load," or the extra mental energy it supposedly takes to lie, and "duping delight," or the pleasure an individual supposedly gets from telling a successful lie.  Wikimedia / Momopuppycat But Ewout Meijer, a professor of psychology at Maastricht University in the Netherlands, says that the grounds for believing such behaviors are universal are unstable at best. The idea that one can find telltale behavioral "leakages" in the face has roots in the work of Paul Ekman, an American psychologist who in the 1980s espoused a now-famous theory of "micro-expressions," or involuntary facial movements too small to control. Ekman's research made him a best-selling author and inspired the TV crime drama Lie to Me. He consulted for myriad US government agencies, including DHS and DARPA. Citing national security, he has kept research data secret. This has led to contentious debate about whether micro-expressions even carry any meaning. Silent Talker's AI tracks all kinds of facial movement, not Ekman-specific micro-expressions. "We decomposed these high level cues into our own set of micro gestures and trained AI components to recombine them into meaningful indicative patterns," a company spokesperson wrote in an email. O'Shea says this enables the system to spot deceptive behavior even when a subject is just looking around or shifting in a chair. "A lot depends on whether you have a technological question or a psychological question," Meijer says, cautioning that O'Shea and his team may be looking to technology for answers to psychological questions about the nature of deception. "An AI system may outperform people in detecting [facial expressions], but even if that were the case, that still doesn't tell you whether you can infer from them if somebody is deceptive … deception is a psychological construct." Not only is there no consensus about which expressions correlate with deception, Meijer adds; there is not even a consensus about whether they do. In an email, the company said that such critiques are "not relevant" to Silent Talker and that "the statistics used are not appropriate."  Fox studios Furthermore, Meijer points out that the algorithm will still be useless at border crossings or in job interviews unless it's been trained on a data set as diverse as the one it will be evaluating in real life. Research shows that facial recognition algorithms are worse at recognizing minorities when they have been trained on sets of predominantly white faces, something O'Shea himself admits. A Silent Talker spokesperson wrote in an email, "We conducted multiple experiments with smaller varying sample sizes. These add up to hundreds. Some of these are academic and have been publish [sic], some are commercial and are confidential." However, all the published research substantiating Silent Talker's accuracy comes from small and partial data sets: in the 2018 paper, for instance, a training population of 32 people contained twice as many men as women and only 10 participants of "Asian/Arabic" descent, with no black or Hispanic subjects. While the software presently has different "settings" for analyzing men and women, O'Shea said he wasn't certain whether it needed settings for ethnic background or age. After the pilot of iBorderCtrl was announced in 2018, activists and politicians decried the program as an unprecedented, Orwellian expansion of the surveillance state. Sophie in 't Veld, a Dutch member of the European Parliament and leader of the center-left Democrats 66 party, said in a letter to the European Commission that the Silent Talker system could violate "the fundamental rights of many border-crossing travelers" and that organizations like Privacy International condemned it as "part of a broader trend towards using opaque, and often deficient, automated systems to judge, assess, and classify people." The opposition seemed to catch the iBorderCtrl consortium by surprise: though initially the European Commission claimed that iBorderCtrl would "develop a system to speed up border crossings," a spokesperson now says the program was a purely theoretical "research project." Antoniades told a Dutch newspaper in late 2018 that the deception-detection system "may ultimately not make it into the design," but, as of this writing, Silent Talker was still touting its participation in iBorderCtrl on its website.

Silent Talker is "a new version of the old fraud," opines Vera Wilde, an American academic and privacy activist who lives in Berlin, and who helped start a campaign against iBorderCtrl. "In some ways, it's the same fraud, but with worse science." In a polygraph test, an examiner looks for physiological events thought to be correlated with deception; in an AI system, examiners let the computer figure out the correlations for itself. "When O'Shea says he doesn't have a theory, he's wrong," she continues. "He does have a theory. It's just a bad theory." However often critics like Wilde debunk it, the dream of a perfect lie detector just won't die, especially when glossed over with the sheen of AI. After DHS spent millions of dollars funding deception research at universities in the 2000s, it tried to create its own version of a behavior-analysis technology. This system, called Future Attribute Screening Technology (FAST), aimed to use AI to look for criminal tendencies in a subject's eye and body movements. (An early version required interviewees to stand on a Wii Fit balance board to measure changes in posture.) Three researchers who spoke off the record to discuss classified projects said that the program never got off the ground—there was too much disagreement within the department over whether to use Ekman's micro-expressions as a guideline for behavior analysis. The department wound down the program in 2011. Despite the failure of FAST, DHS still shows interest in lie detection techniques. Last year, for instance, it awarded a $110,000 contract to a human resources company to train its officers in "detecting deception and eliciting response" through "behavioral analysis." Other parts of the government, meanwhile, are still throwing their weight behind AI solutions. The Army Research Laboratory (ARL) currently has a contract with Rutgers University to create an AI program for detecting lies in the parlor game Mafia, as part of a larger attempt to create "something like a Google Glass that warns us of a couple of pickpockets in the crowded bazaar," according to Purush Iyer, the ARL division chief in charge of the project. Nemesysco, an Israeli company that sells AI voice-analysis software, told me that its technology is used by police departments in New York and sheriffs in the Midwest to interview suspects, as well as by debt collection call centers to measure the emotions of debtors on phone calls. The immediate and potentially dangerous future of AI lie detection is not with governments but in the private market. Politicians who support initiatives like iBorderCtrl ultimately have to answer to voters, and most AI lie detectors could be barred from court under the same legal precedent that governs the polygraph. Private corporations, however, face fewer constraints in using such technology to screen job applicants and potential clients. Silent Talker is one of several companies that claim to offer a more objective way to detect anomalous or deceptive behavior, giving clients a "risk analysis" method that goes beyond credit scores and social-media profiles.

A Montana-based company called Neuro-ID conducts AI analysis of mouse movements and keystrokes to help banks and insurance companies assess fraud risk, assigning loan applicants a "confidence score" of 1 to 100. In a video the company showed me, when a customer making an online loan application takes extra time to fill out the field for household income, moving the mouse around while doing so, the system factors that into its credibility score. It's based on research by the company's founding scientists that claims to show a correlation between mouse movements and emotional arousal: one paper that asserts that "being deceptive may increase the normalized distance of movement, decrease the speed of movement, increase the response time, and result in more left clicks." The company's own tests, though, reveal that the software generates a high number of false positives: in one case study where Neuro-ID processed 20,000 applications for an e-commerce website, fewer than half the applicants who got the lowest scores (5 to 10) turned out to be fraudulent, and only 10% of the those who received scores from 20 to 30 represented a fraud risk. By the company's own admission, the software flags applicants who may turn out to be innocent and lets the company use that information to follow up how it pleases. "There's no such thing as behavior-based analysis that's 100% accurate," a spokesperson told me. "What we recommend is that you use this in combination with other information about applicants to make better decisions and catch [fraudulent clients] more efficiently." |

| You are subscribed to email updates from "lie detector test online" - Google News. To stop receiving these emails, you may unsubscribe now. | Email delivery powered by Google |

| Google, 1600 Amphitheatre Parkway, Mountain View, CA 94043, United States | |

Comments

Post a Comment