Do Lie Detector Tests Really Work? - Psychology Today

Do Lie Detector Tests Really Work? - Psychology Today |

- Do Lie Detector Tests Really Work? - Psychology Today

- Researchers Built an ‘Online Lie Detector.’ Honestly, That Could Be a Problem - WIRED

- Polygraph lie detector tests: Can they really stop criminals reoffending? - Phys.org

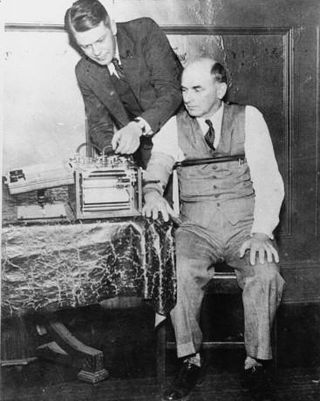

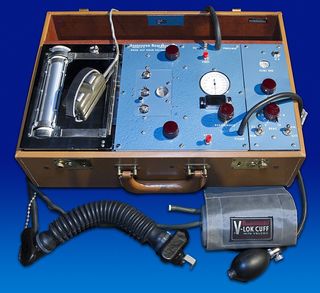

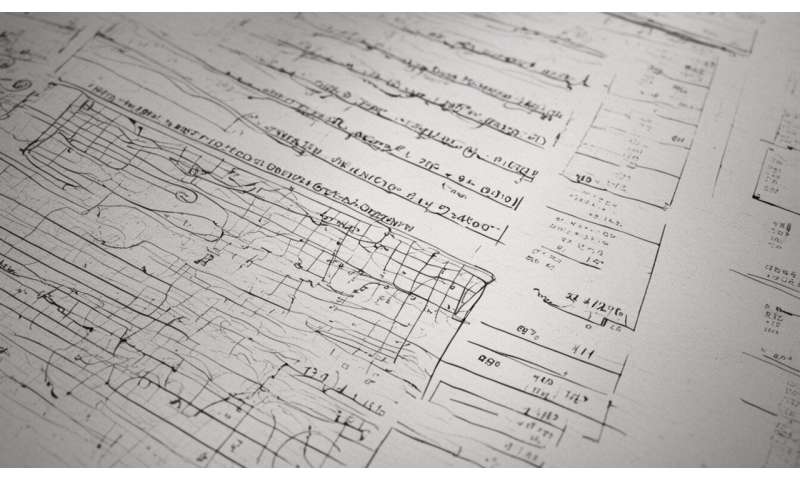

| Do Lie Detector Tests Really Work? - Psychology Today Posted: 14 Jan 2020 12:00 AM PST In February of 1994, the FBI arrested Aldrich Ames, who had been a CIA employee for 31 years. Ames was arrested and charged with espionage. He was a Russian spy. For nine years, he had been passing secrets to the Russians in exchange for over $1.3 million. His spying activities had compromised dozens of CIA and FBI operations. Worse yet, his treacherous crimes had led to the deaths of several CIA spies and the imprisonment of many more. During the time that Aldrich Ames was operating as a Russian spy, the CIA had twice given him a lie detector test. Despite having no special training in how to defeat a lie detector test, Aldrich passed both times.  Source: wikimedia The modern polygraph, better known as the "lie detector test," is a fascinating little instrument with a long and controversial history. The earliest version a polygraph instrument was developed in 1921 when John Larson cobbled together previously developed measures of respiration, heart rate, and blood pressure that had individually shown promise as a measure of lying. Technological developments continued, and the modern polygraph is now an integrated, state-of-the-art, computerized system that continuously monitors blood pressure, heart rate, respiration, and perspiration. The theory behind the polygraph is that when people are lying, they experience a different emotional state than when they are telling the truth. Specifically, it is thought that when people are lying, especially in high stakes scenarios such as police interrogations, they are anxious or afraid of being caught in a lie. When guilty people are asked questions that would reveal their guilt (e.g., Where were you last Tuesday?), and they lie, the fear of being detected causes increased activation of their sympathetic nervous system. This activation leads to an increase in heart rate, blood pressure, respiration, and perspiration. These changes are part of the fight-or-flight system that initiates whenever was are scared. You have probably felt your heart pounding or your palms sweating when faced with danger, be it a vicious dog, an angry boss, or an upcoming exam.  Source: wikimedia The polygraph is designed to detect those subtle changes in a person's physiological responses when they lie. The general idea is that when a person is being honest, their physiological responses remain stable under questioning, whereas a guilty person's heart will race. One of the most common polygraph procedures is called the comparison question test (also called the control question test). The examinee is asked relatively benign questions such as "Where do you live." They are also asked questions that are not relevant to the crime, but which would likely trigger an emotional reaction such as, "Have you ever told a lie?" They are then asked questions about the alleged crime such as, "Did you steal the documents?" The premise of the comparison question test is that a guilty person will have a much stronger physiological reaction to the crime question, whereas an innocent person will not. The polygraph is used in criminal investigations, although it is generally not admissible as evidence in a trial. It is also used as a pre-employment and continuing employment screening tool for many federal employees who work in sensitive positions, such as CIA agents and FBI agents. Private businesses, however, cannot force their employees to submit to a polygraph test. So, does the polygraph actually work? Are the results accurate? It does work much of the time. Typically, when someone is lying, a well-trained polygraph examiner can tell. It is not 100% accurate though. The American Polygraph Association is the world's leading association dedicated to the use of evidence-based scientific methods for credibility assessment. It is an organization whose members are largely polygraph examiners. They estimate the accuracy of the polygraph to be 87%. That is, in 87 out of 100 cases, the polygraph can accurately determine if someone is lying or telling the truth. That sounds pretty impressive, but it is important to keep in mind that the polygraph is failing 13% of the time. The federal government sought an unbiased evaluation of the polygraph, so they tasked the National Academy of Sciences with a full investigation of the polygraph's accuracy. In 2003, this large team of notable scientists came to the conclusion that the polygraph was far less accurate than the polygraph examiners had claimed. Some scientists have claimed that the accuracy may be closer to 75%. This lackluster performance is the reason why polygraphs are not used as evidence in criminal trials. They just cannot be trusted.  Source: wikimedia For more clear evidence that the polygraph is unreliable, just look back to the Alrich Ames case mentioned at the top of this article. Ames lied during his polygraph examinations at the CIA, and he passed each time. In this case, the lie detector test failed. When asked how he passed the polygraph test, Ames said that he followed the advice of his Russian handlers. They told him, "Just relax, don't worry, you have nothing to fear." The Russians knew that the polygraph was flawed. They knew that it was only accurate if the examinee was worried and anxious. They knew that if Ames could just relax, he would pass. |

| Researchers Built an ‘Online Lie Detector.’ Honestly, That Could Be a Problem - WIRED Posted: 21 Mar 2019 12:00 AM PDT  The internet is full of lies. That maxim has become an operating assumption for any remotely skeptical person interacting anywhere online, from Facebook and Twitter to phishing-plagued inboxes to spammy comment sections to online dating and disinformation-plagued media. Now one group of researchers has suggested the first hint of a solution: They claim to have built a prototype for an "online polygraph" that uses machine learning to detect deception from text alone. But what they've actually demonstrated, according to a few machine learning academics, is the inherent danger of overblown machine learning claims. In last month's issue of the journal Computers in Human Behavior, Florida State University and Stanford researchers proposed a system that uses automated algorithms to separate truths and lies, what they refer to as the first step toward "an online polygraph system—or a prototype detection system for computer-mediated deception when face-to-face interaction is not available." They say that in a series of experiments, they were able to train a machine learning model to separate liars and truth-tellers by watching a one-on-one conversation between two people typing online, while using only the content and speed of their typing—and none of the other physical clues that polygraph machines claim can sort lies from truth. "We used a statistical modeling and machine learning approach to parse out the cues of conversations, and based on those cues we made different analyses" of whether participants were lying, says Shuyuan Ho, a professor at FSU's School of Information. "The results were amazingly promising, and that's the foundation of the online polygraph." But when WIRED showed the study to a few academics and machine learning experts, they responded with deep skepticism. Not only does the study not necessarily serve as the basis of any kind of reliable truth-telling algorithm, it makes potentially dangerous claims: A text-based "online polygraph" that's faulty, they warn, could have far worse social and ethical implications if adopted than leaving those determinations up to human judgment. "It's an eye-catching result. But when we're dealing with humans, we have to be extra careful, especially when the implications of whether someone's lying could lead to conviction, censorship, the loss of a job," says Jevin West, a professor at the Information School at the University of Washington and a noted critic of machine learning hype. "When people think the technology has these abilities, the implications are bigger than a study." Real or Spiel The Stanford/FSU study had 40 participants repeatedly play a game that the researchers called "Real or Spiel" via Google Hangouts. In the game, pairs of those individuals, with their real identities hidden, would answer questions from the other in a kind of roleplaying game. A participant would be told at the start of each game whether they were a "sinner" who lied in response to every question, or a "saint" who always told the truth. The researchers then took the resulting textual data, including the exact timing of each response, and used a portion of it as the training data for a machine learning model designed to sort sinners from saints, while using the rest of their data to test that model. They found that by tuning their machine learning model, they could identify deceivers with as much as 82.5 percent accuracy. Humans who looked at the data, by contrast, barely performed better than guessing, according to Ho. The algorithm could spot liars based on cues like faster answers than truth-tellers, a greater display of "negative emotions," more signs of "anxiety" in their communications, a greater volume of words, and expressions of certainty like "always" and "never." Truth-tellers, by contrast, used more words of causal explanation like "because," as well as words of uncertainty, like "perhaps" and "guess." The algorithm's resulting ability to outperform humans' innate lie detector might seem like a remarkable result. But the study's critics point out that it was achieved in a highly controlled, narrowly defined game—not the freewheeling world of practiced, motivated, less consistent, unpredictable liars in real world scenarios. "This is a bad study," says Cathy O'Neill, a data science consultant and author of the 2016 book Weapons of Math Destruction. "Telling people to lie in a study is a very different setup from having someone lie about something they've been lying about for months or years. Even if they can determine who's lying in a study, that has no bearing on whether they'd be able to determine if someone was a more studied liar." |

| Polygraph lie detector tests: Can they really stop criminals reoffending? - Phys.org Posted: 24 Jan 2020 12:00 AM PST  The UK government recently announced it was planning to increase the use of polygraphs to monitor offenders on probation, specifically those convicted of terrorist offenses. This is one of several new measures to prevent a repeat of the recent London Bridge attack, which was committed by an offender out in the community on license. One difficulty with deciding which offenders can be released this way is that offenders can lie about their actions, thoughts and intentions to convince probation officers that they pose a low risk. The government hopes that an increased use of polygraphs will help identify terrorists planning to reoffend. But are polygraphs actually able to do this? Polygraphs are already in use in the UK for probation purposes. Since 2014, high-risk sex offenders have had to undergo polygraphs testing as part of their license conditions. Sex offenders are also routinely asked to undergo polygraphs in the US, but the practice is not common in other countries. Although polygraphs are sometimes known as lie detectors, they don't actually detect lies directly. Most modern polygraphs measure the interviewee's heart rate, breathing rate and sweating while they are asked yes/no questions. These questions need to be simple and refer to a concrete event that is known by the interviewer. This makes it hard to use polygraphs to ask people what they plan to do in the future, because we don't know enough to know the right questions to ask. The polygraph picks up on any changes in breathing, heart or sweat rate during the interview. These changes can happen for many reasons. Sometimes a response is caused by the stress of lying. Sometimes they are an "orienting response", people responding to something familiar or important to them. This can be helpful to show that somebody knows something that they said they didn't know ("guilty knowledge"). However, strong polygraph responses may also be due to shock or upset at the question or nervousness about the polygraph itself. Better than average So how accurate are polygraphs in actually detecting lies? There have been several reviews of polygraph accuracy. They suggest that polygraphs are accurate between 80% and 90% of the time. This means polygraphs are far from foolproof, but better than the average person's ability to spot lies, which research suggests they can do around 55% of the time. However, many of these polygraph studies involved people lying about clearly defined events in controlled experiments. It is possible that polygraphs are less accurate in real life probation cases. One study from 2006 attempted to estimate the accuracy of the polygraph with US sex offenders, but it relied on the offenders saying when the polygraph was wrong, which may not be entirely accurate. Unfortunately, we don't know how often probation officers suspect that offenders are lying and how good they are at identifying lies. So, we don't know whether polygraphs are better than probation officers. There are also concerns about when the polygraph is wrong. The test can be beaten by liars with knowledge of how polygraphs work and are used. These people may also be the ones that the probation officers are most interested in catching. They may have practiced how to beat polygraphs precisely because they have very serious things to hide. Some studies show that polygraphs are worse at detecting that people are telling the truth than detecting they are lying, in some cases indicating deception for almost half of the people who are actually telling the truth. This can be especially difficult to deal with in probation situations, where an offender may have no opportunity to prove that they were not lying when the polygraph indicates they are. How do you prove that you weren't planning to reoffend? Encouraging truth telling However, there is another use for polygraphs in probation. They encourage people to confess. Forensic psychologist Theresa Gannon and her colleagues studied this on UK sex offenders in 2014. They found that offenders were more likely to disclose something of interest when using the polygraph (75%, instead of 51% without). This disclosure often happened after the polygraph had indicated deception. It may be that offenders feel forced to make a confession after failing the polygraph. However, the study could not tell whether these confessions are true. After failing a polygraph, offenders may feel that further denials won't be believed and confessing is best, even when they were not lying. This research suggests that the polygraph can be used to psychologically pressure offenders into disclosing self-incriminating information. Information that may not even be true. So, is it a good idea for the government to increase polygraph use to monitor offenders? Research shows that they are nowhere near foolproof, but they may have some usefulness as a potential indicator of deception and to encourage truth telling. However, using them raises several ethical questions. For example, it is fair to use them to try and extract self-incriminating statements? Some people may argue that something is better than nothing and polygraphs are the best we've got. But in instances where polygraphs are so inaccurate that they give probation officers more useless than useful information, nothing may be better than something. Explore further Provided by The Conversation This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article. Citation: Polygraph lie detector tests: Can they really stop criminals reoffending? (2020, January 24) retrieved 25 September 2020 from https://phys.org/news/2020-01-polygraph-detector-criminals-reoffending.html This document is subject to copyright. Apart from any fair dealing for the purpose of private study or research, no part may be reproduced without the written permission. The content is provided for information purposes only. |

| You are subscribed to email updates from "lie detector test online" - Google News. To stop receiving these emails, you may unsubscribe now. | Email delivery powered by Google |

| Google, 1600 Amphitheatre Parkway, Mountain View, CA 94043, United States | |

Comments

Post a Comment