Cara Delevingne, Orlando Bloom Talk Hannah Montana, T.Swift and More - E! NEWS

Cara Delevingne, Orlando Bloom Talk Hannah Montana, T.Swift and More - E! NEWS |

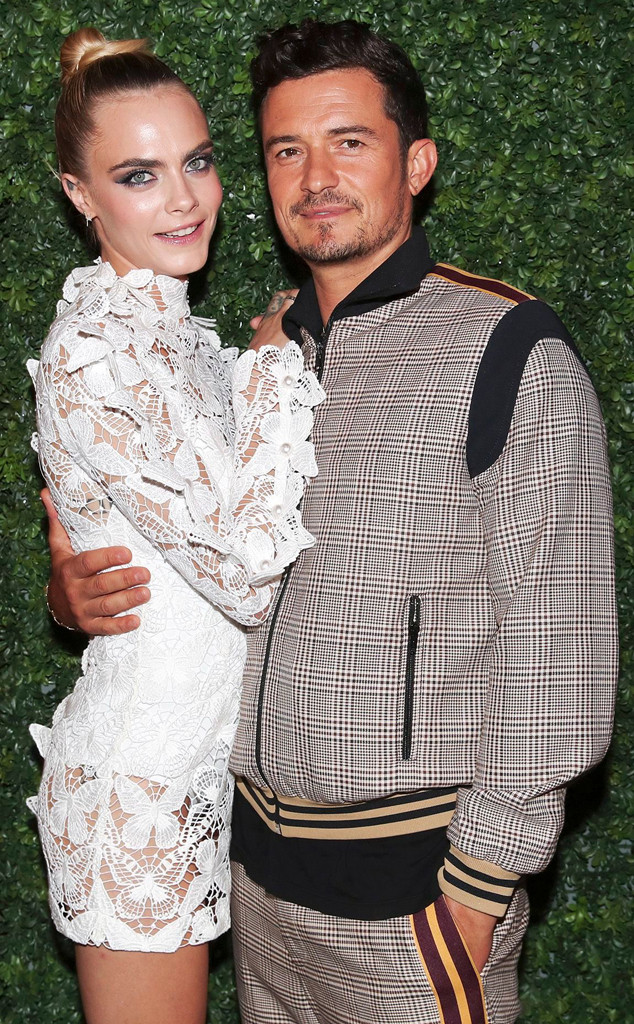

| Cara Delevingne, Orlando Bloom Talk Hannah Montana, T.Swift and More - E! NEWS Posted: 30 Aug 2019 11:10 AM PDT  Chris Polk/JanuaryImages/Shutterstock Cara Delevingne and Orlando Bloom are taking a lie detector test! In a new video for Vanity Fair, posted on YouTube Friday, the Carnival Row co-stars grill each other about everything from pop music and Hannah Montana to Rihanna and Taylor Swift. The video shows Bloom taking on the lie detector first, answering questions from Delevingne, who asks him about the Hannah Montana song, "The Best of Both Worlds." When asked whether it's ever been brought to his attention that he's "name-dropped" in the song, Bloom replies, "No." A clip from the song is then played, and, to Bloom's surprise, his name is mentioned. "Oh my God!" Bloom laughs. "That's crazy." "In that song, Hannah Montana sings, 'Being famous is kind of fun,'" Delevingne tells Bloom. "Would you agree with that sentiment?" "No," Bloom replies. When asked what's the "best part" of being famous, Bloom shares, "Getting a table at a restaurant...last minute." After Bloom, it's Delevingne's turn to take the lie detector test! Check out the video above to see who Delevingne would rather be "trapped in the wilderness" with: Rihanna or T.Swift! Plus, find out if Bloom is really a fan of pop music! Don't miss E! News every weeknight at 7, only on E! |

| The Online Lie Detector Is No Better Than the Polygraph - JSTOR Daily Posted: 02 May 2019 12:00 AM PDT Artificial Intelligence researchers recently announced a prototype for an "online lie detector." Experts say it probably doesn't actually work that well in the real world. Then again, the historian Ken Adler writes, that didn't stop the old-fashioned polygraph from gaining enormous popularity. According to Adler, in the second half of the nineteenth century, some European psychologists began monitoring patients' blood pressure, respiration, and pulse rates, investigating the way these physical signs correlated with emotional changes, tension, or reactions to sharp noises. In the 1910s, Hugo Münsterberg, a German-American psychologist, and his student William Moulton Marston began using these tests to attempt to determine whether witnesses were lying about criminal matters. Marston would go on to create Wonder Woman, with her Lasso of Truth. American police reformers popularized the polygraph test as an alternative to brutal police interrogations in the 1920s and 30s. Before long, polygraph use spread to the State Department—which used it to screen civil servants suspected of homosexuality—and to corporate America. By the middle of the century, cops, managers, and industrial psychologists were conducting two million polygraph exams a year. Alder writes that the machines appealed to a growing public desire for "a dispassionate search for truth conducted by impersonal rules." That reflected a broader trend at a time when cities and businesses were becoming larger, making it impossible to rely on personal trust. The contemporaneous rise of intelligence testing, industrial management techniques, and other "scientific" methods for managing human behavior spoke to the desire to make sense of an increasingly complicated world. And yet, for all its associations with the objective pursuit of the truth, several prominent proponents of the polygraph acknowledged that the machine would work only if its subjects believed in it. To make that happen, they used deceptions of their own. For example, polygraph entrepreneur Leonarde Keeler used a marked deck of cards to convince subjects that he could tell whether they were lying about which card they were looking at. Then and today, Alder argues, the actual functioning of the machines was almost beside the point. Some police examiners have achieved the same result—convincing a suspect to confess—by having them place their hands on a photocopy machine which then produces a paper printed with "LIAR!" Weekly DigestFrom the beginning, judges rejected the use of lie detectors in courtroom trials, but allowed police to use them to extract confessions. Since the vast majority of criminal convictions occur not through trials but through confessions and plea bargains, that's generally good enough for cops and prosecutors. By the time Alder was writing, in 2002, the use of the polygraph in corporate settings was declining, and the general public was becoming more skeptical of its value in criminal cases. Still, as the buzz around the new online lie detector suggests, people love the idea of a machine that tells us who to trust. |

| You are subscribed to email updates from "lie detector test online" - Google News. To stop receiving these emails, you may unsubscribe now. | Email delivery powered by Google |

| Google, 1600 Amphitheatre Parkway, Mountain View, CA 94043, United States | |

Comments

Post a Comment